|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

The NASA budget process is fairly confusing and the way that media reports on it doesn't make things better. This short video is my attempt to reduce the confusion.

This isn't going to be terribly exciting, therefore we're going to start with an Atlas Centaur test from 1962...

Now onto the budget stuff.

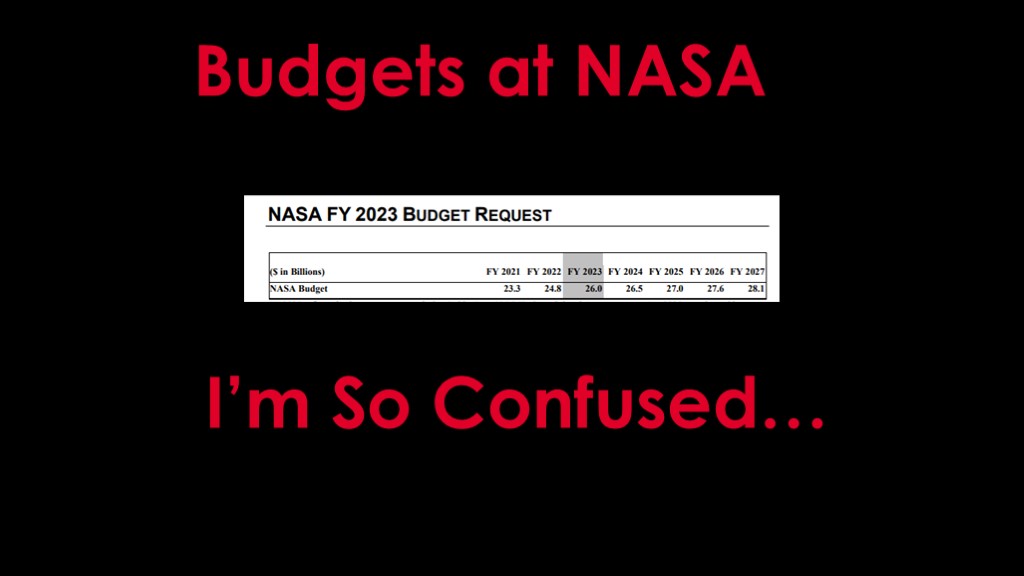

We'll start with the NASA fiscal year 2023 budget estimates, a 990 page document that both summarizes all the programs NASA is working on and provides estimates for how much they will cost for 2023.

It would be more correct to replace the word "Estimates" with one of the following:

Dreams

Hopes

Wishes

I'll explain why in a minute...

https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy23_nasa_budget_request_full_opt.pdf

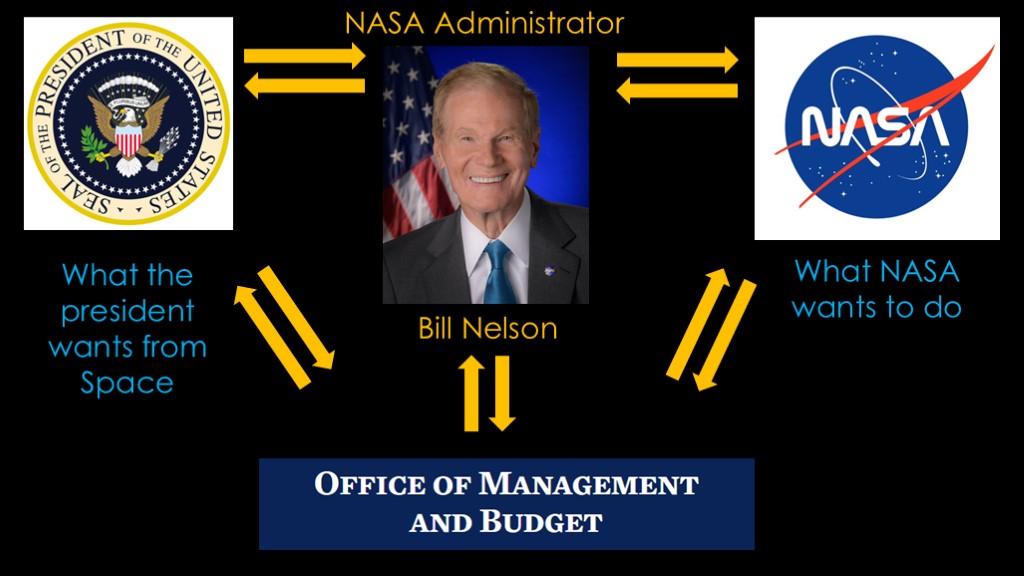

Here's how that budget document is created...

NASA is part of the Executive branch, and therefore is managed by the President. In between the president and NASA is the NASA administrator, currently former astronaut and Florida Senator Bill Nelson. You can think of his job as "NASA CEO"; he's in charge of the overall operation of the agency.

The third player in this process is the office of management and budget.

There are discussions between all of these entities; the president has specific ideas of what they want from space, and NASA has ideas on what they want to do, and OMB understands the fiscal realities, and all of those concerns get iterated and refined, and out of the process comes the NASA budget, plus the budgets for the rest of the government.

However...

The constitution says that it isn't the president that decides what money to spend, it's Congress.

That is why the NASA budget is aspirational; it describes what NASA is *hoping* to get.

The senate and house therefore control how much money NASA gets...

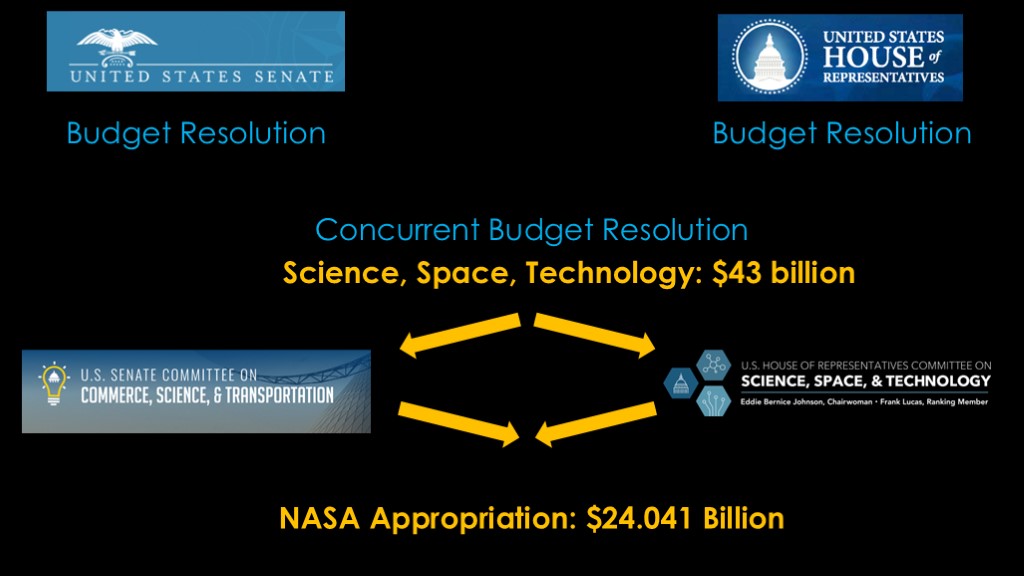

To start, both the senate and house create a budget resolution, which is a high-level overview that describes how money will be spent across the government.

These then feed into a joint working group, and the house and senate agree on a Concurrent budget resolution.

But that general resolution has very little detail; it will only say that science, space, and technology will get $43 billion.

Those high level numbers then get sent back to the senate and house, to the committees that own deciding the specifics of how that money will be allocated.

Their decisions then feed back into another shared process to reconcile their different numbers, and that ultimately leads to the NASA appropriations; a detailed budget for how much money NASA has for a fiscal year.

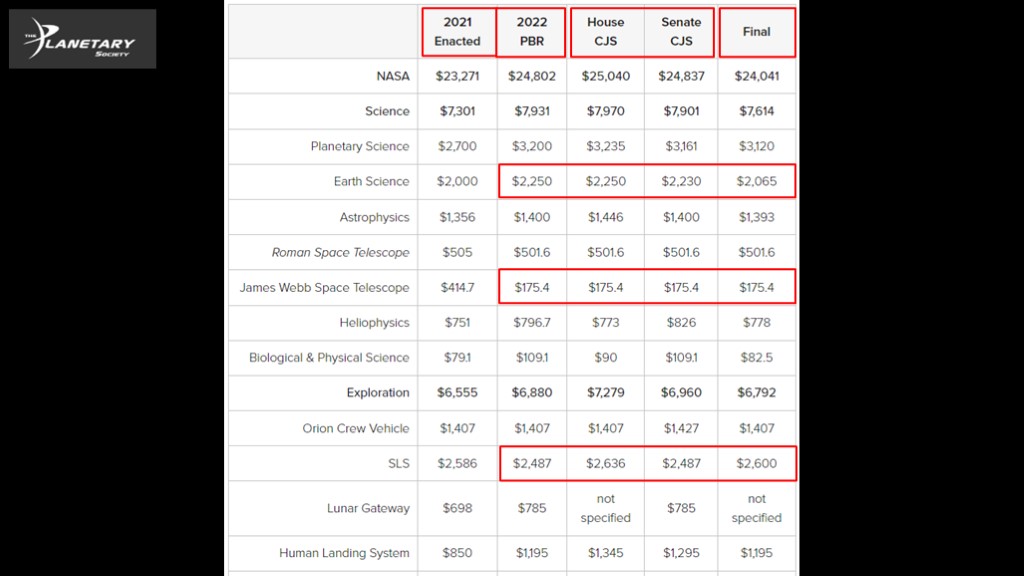

The planetary society nicely provides a summary of the appropriations. Here you can see part of the appropriations for 2022; the table shows the following values:

The first column shows the amount of money that was appropriated in 2021, where "appropriated" means "given to NASA to spend".

The next column shows the president's budget request for 2022.

The next two columns show the house and senate appropriations, which is how much each of the committees thought NASA should spend on individual programs.

The final column shows the amount of money actually appropriated.

Let's look at three programs...

The james webb space telescope is flat across the board; NASA wanted $175.4 million and everybody agreed on that figure.

SLS got more than they requested.

And if you look at the earth science amount, both the senate and house thought the request was reasonable, but when they got together they knocked a few hundred million off of it. That is - as they say - how politics works

https://www.planetary.org/space-policy/nasas-fy-2022-budget

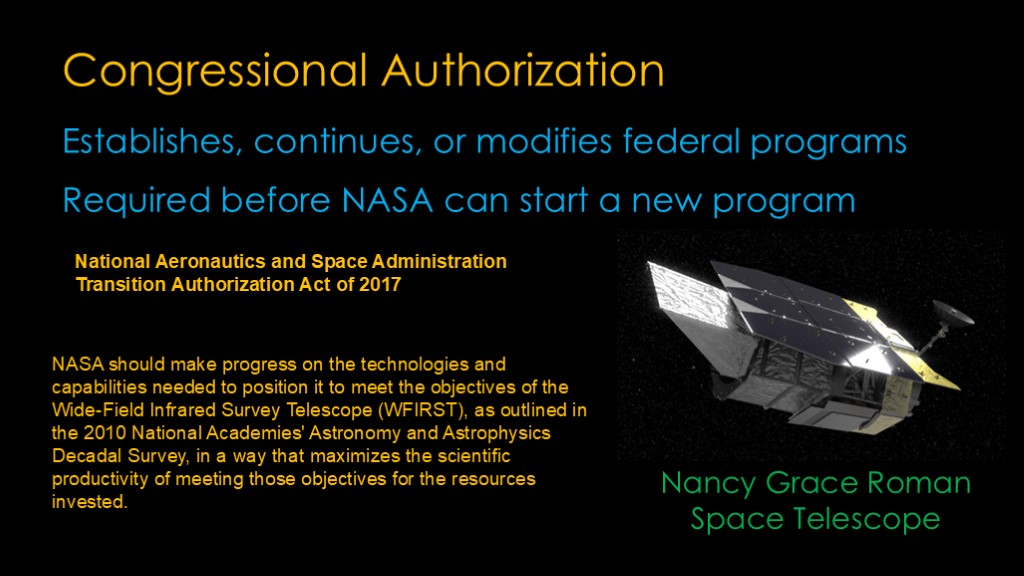

Congressional authorization is a separate process, and it is the way that congress establishes, continues, or modifies federal programs.

NASA cannot start new projects without this authorization.

For example, the NASA authorization act of 2017 said:

(read)

That gave permission for NASA to begin developing what is now known as the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

Nancy Grace Roman was the first female executive at NASA, and served as NASA's first Chief of Astronomy throughout the 1960s and 1970s, establishing her as one of the "visionary founders of the US civilian space program".

She created NASA's space astronomy program and is known to many as the "Mother of Hubble" for her foundational role in planning the Hubble Space Telescope.

NASA cannot start new programs without authorization, but authorization does not provide any money.

What matters is the money that gets appropriated.

Or as immortalized in "The Right Stuff"...

Here are some examples of weirdness, either in the budgetary process or in the reporting of it.

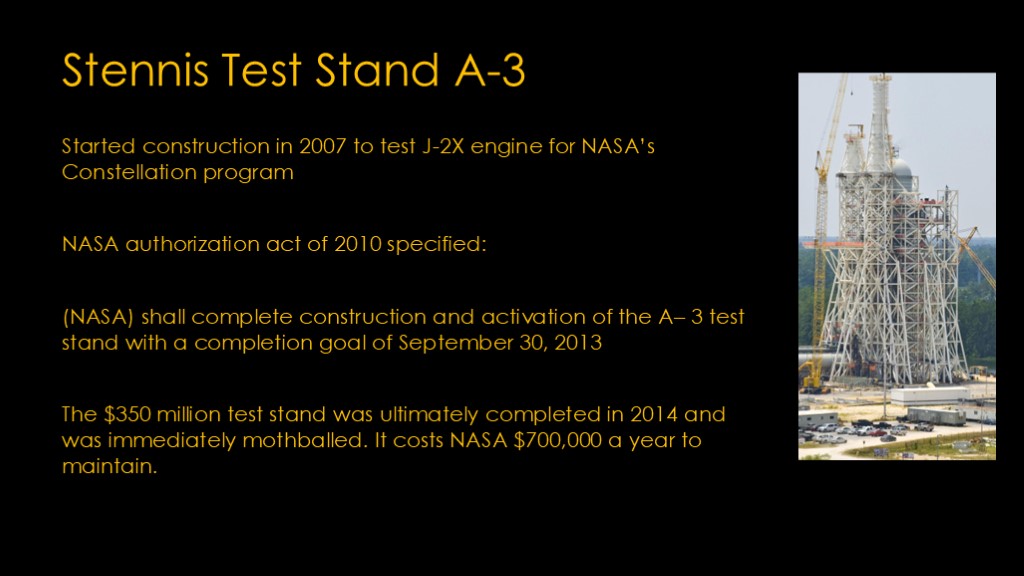

The A-3 test stand at Stennis started construction in 2007 to test the J-2X engine for NASA's constellation program.

Constellation was cancelled and NASA is no longer has plans to use the J-2X, but the NASA authorization act of 2010 specified that NASA would continue to complete the construction and activation of the A-3 test stand.

The $350 million test stand was completed in 2014 and mothballed; it now costs NASA $700,000 each year to maintain.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2014/12/15/nasas-349-million-monument-to-its-drift/

NASA's original SLS plans were to take the SLS block 1 mobile launcher and modify it to support block to, but Congress instead decided to appropriate money for a second mobile launcher, at an estimated cost of $450 million.

SOFIA, an airborne telescope project, was eliminated from the 2022 budget request, but congress decided to keep it alive by funding it at $85 million

The Nuclear Thermal Propulsion project was also eliminated in the 2022 budget request, but congress decided to fund it at $110 million.

Here's a recent story...

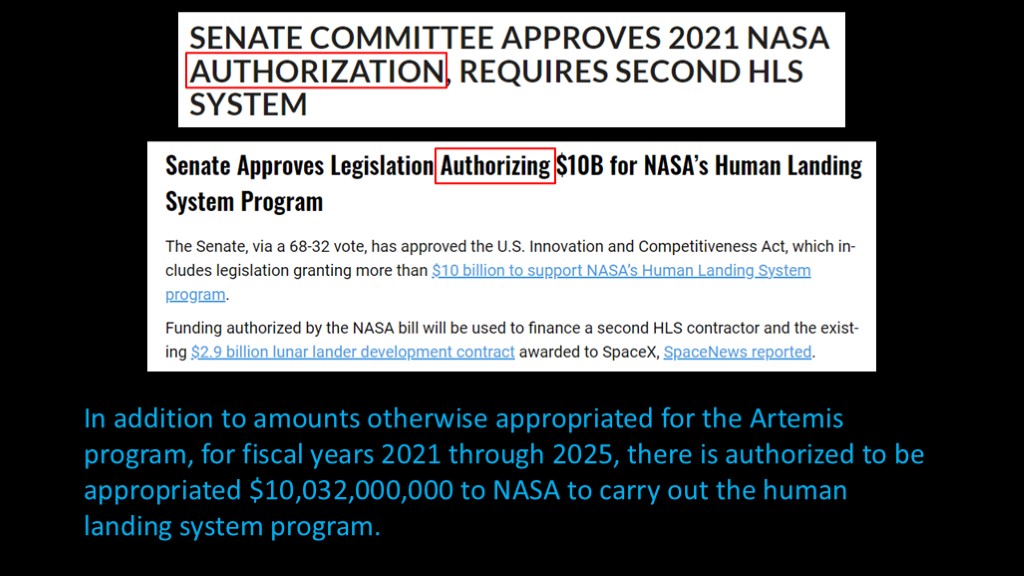

Senate committee approves 2021 NASA authorization, requires second HLS system.

And another one, which says...

... legislation granting more then $10 billion to support NASA's Human Landing System program.

Let's look at the actual text of the authorization bill.

These give the distinct impression that NASA would be making a second award with a significant amount of money. But I'm sure you noticed the specific word used:

Authorization.

This bill is about authorization. The fact that it gives a dollar amount is simply a smokescreen; authorization bills do not appropriate money.

What happened?

Both the house and senate allocated $100 - 150 million extra for HLS in committee, but the final number is the original $1,195 requested by NASA.

Authorization does not equal appropriation

And finally, we come to the NASA authorization act of 2010, which contains authorization for two programs.

First, it authorizes a new follow-on program to the space shuttle known as the Space Launch System.

And second, it authorizes NASA to expand the size of the commercial crew program that had just been started.

But we all know what "authorization" means. How were these two programs appropriated?

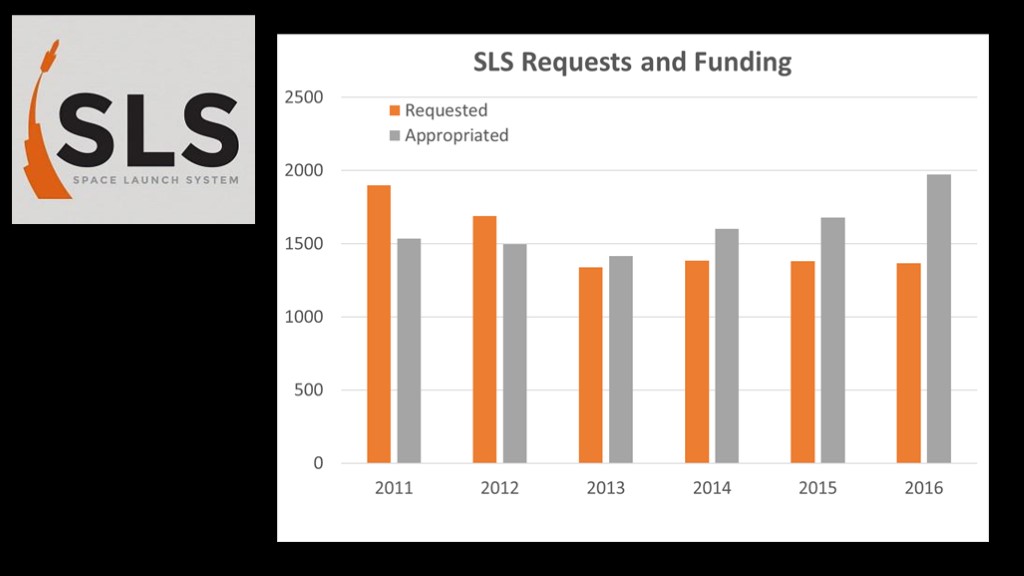

Here's a graph showing the SLS budget requests and appropriation amounts. In 2011 and 2012 the amount appropriated was a little bit less than the request, but since then, congress has consistently appropriated more money for SLS than NASA has requested.

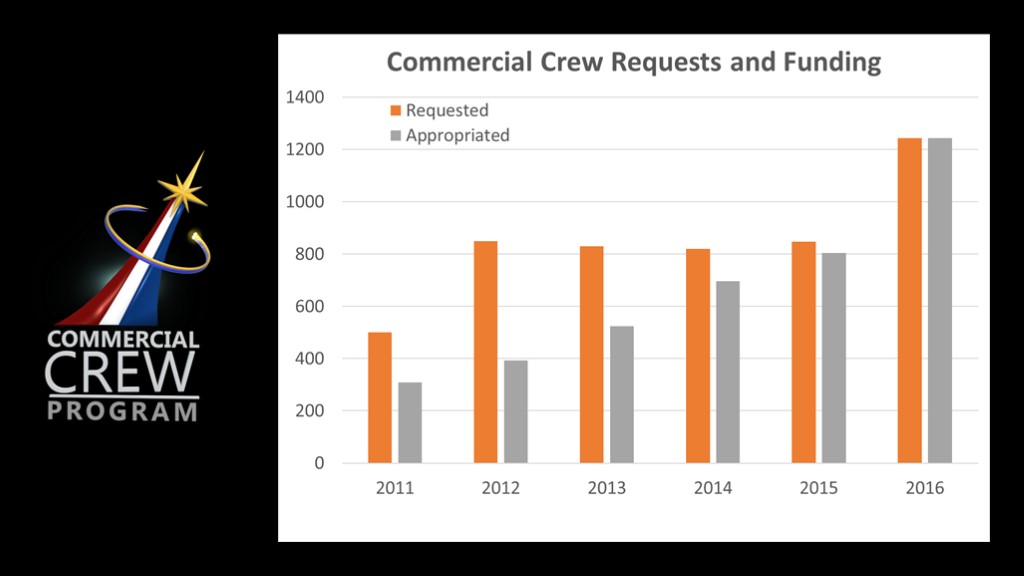

Commercial crew was quite different.

In 2011 through 2015, congress appropriated 60%, 45%, 65%, 85%, and 95% of what NASA had requested, and only reached parity in 2016. This lack of money slowed down progress on Commercial Crew significantly.

Here's my quick summary.

NASA budgets are aspirational; it is what NASA is hoping to get.

Congress controls what programs exist and how much money they get. They can decide to fund projects that NASA isn't interested in, not fund projects that NASA wants to do, or underfund projects that they explicitly told NASA to do.

Don't pay attention to stories about authorization bills.

Pay attention to appropriations; that is how congress indicates what is important to them and the actual NASA budget.

If you enjoyed this video, please compose a NASA budget haiku...